Category: Cloud

Cloud migration typically refers to the process of moving digital assets- like Data, workloads, IT resources, or application from on-premises to the cloud infrastructure. According to Gartner, Inc. forecast, the worldwide public cloud service market has grown 17% in 2020 to a total of $266.4* billion. But the problem is in migrating applications to the public cloud, IT teams are confronting two separate but related issues that add costs and complexity: refactoring and repatriation. Let us look at the reasons behind avoid refactoring and repatriation before we delve into the probable solutions for the cloud migration journey.

Why business avoid Refactoring

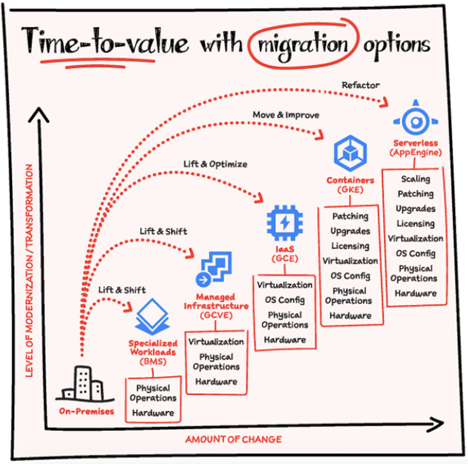

Refactoring applications frequently happen when you are looking at custom-built apps. With the approach of refactoring, you will have to rewrite the code and completely re-engineer your application from scratch to make the application more cloud ready. APIs and integrations with computing, storage, and network resources are also included under the refactoring process.

Refactoring turns legacy apps into cloud-native apps, makes it more feasible for developers to use modern tools such as containers and microservices, and saves money in the long run. Although this approach makes an application more scalable and responsive than on-premises counterparts, it takes a lot of additional time and resources, meaning your upfront costs are going to be much higher. The chances of risks are high because the IT team needs to be careful that they are not impacting the external behavior of the application while rewriting the code.

IT team can apply the lift and shift method for moving an application from the data center to the cloud and avoid the process of refactoring completely. This method simplifies the migration process, saves time and cost, and accelerates the shift to the cloud. They can also use pervasive automation to make the lift-and-shift migration as seamless as possible.

Apart from that, IT consultants can leverage a cloud platform that tightly integrates on-premises infrastructure with cloud management software. By using the Microsoft Azure platform as a migration path, IT can build a cloud strategy that delivers agility and cost optimization. This holistic approach will not only help you navigate the journey successfully but also ensure that your organization releases new benefits including, agility, scale, and efficiency, especially when your workloads are running in the cloud.

Why business avoid Repatriation

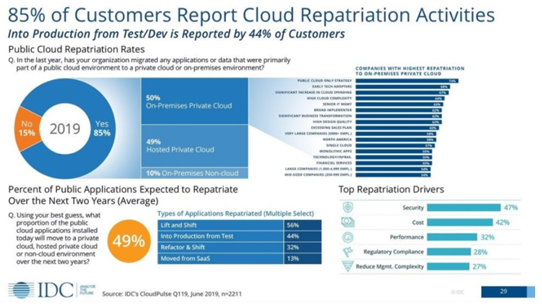

“Unclouding” or “repatriation” is the process of pushing back application workloads and data from the public cloud to local infrastructure environments within an on-premises data center. As mentioned by TechTarget, concerns about operating costs, availability, changing business needs, security and compliance, and cloud-based workload performance are the most common reasons for repatriation.

Repatriation is also too expensive and time consuming that businesses want to avoid. Initially, the organizations go through the expense of migrating an app to the cloud then they realize it is spending too much money in the cloud and bearing other issues. Finally, they decide to go through the expense of migrating that application back to the data center. The whole process ultimately creates a lot of difficulties and confusion for the business.

The cost of repatriation may vary as per the application, workload, and company infrastructure. According to a survey result, one company can save almost $75** million in infrastructure costs over two years by moving apps to the data center from the cloud. Moreover, it would reduce operational costs 66% by reducing downtime and increasing capacity by 25%**. Sometimes even IT experts face troubles understanding the complexities of the public cloud. AWS, Azure, and other public cloud vendors are even offering a gateway to the public cloud and back with solutions like AWS Outpost and Azure Stack. Businesses can consider using Azure Import/Export to securely import or export large amounts of data to Azure Blob storage and Azure files by shipping disk drives to an Azure data center.

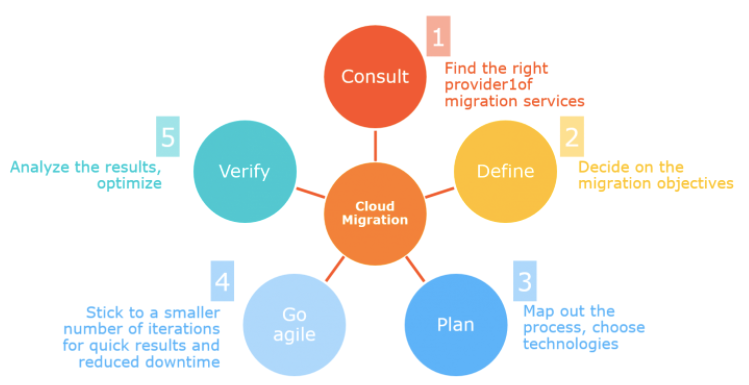

Simplifying the cloud migration path The migration to the cloud does not have to be difficult if an organization executed proper planning. Choosing the right cloud platform can also increase speed and reduce risk. We hope the below three simple steps will help every enterprise in advanced migration.

Step 1: Assess your application inventory carefully

First, an organization needs to plan a proper assessment that will categorize the application portfolio into different groups (like modern apps, legacy apps, or everything else including, Java, .NET, web applications) and include an assessment of the dependencies or ecosystem around the application. In Inovar Consulting, we first communicate with our clients to understand the physical and virtual server configurations, security and compliance requirements, existing support, network topology, and data dependencies. It helps us to see where to begin for maximum results and create a proper strategy plan as per the present needs.

Step 2: Create a proper plan

The best way to avoid the costs and complexities of refactoring and repatriation is to do a thorough analysis of the applications. Before suggesting any migration path, we ask the below questions and encourage our customers to think beyond the applications.

- What are the business goals, and why are you considering the cloud?

- What is the architecture of the application? Does it follow the cloud-native principles for high availability?

- What are the interdependencies between each app and workload?

- What tools are being used to manage and enforce the security policies around the application?

- How much will the migration cost and, once it is completed, what will be the ongoing operational costs?

- How much you aware of the underlying topology and performance characteristics?

You have to prioritize the migration based on the answers to this question. For example, you may decide that the application is better served by incorporating public cloud services in a hybrid cloud model that involves a lift-and-shift migration. Or if the analysis determines that refactoring is mandatory then, it is vital to choose the right migration path so you can avoid repatriation in the future.

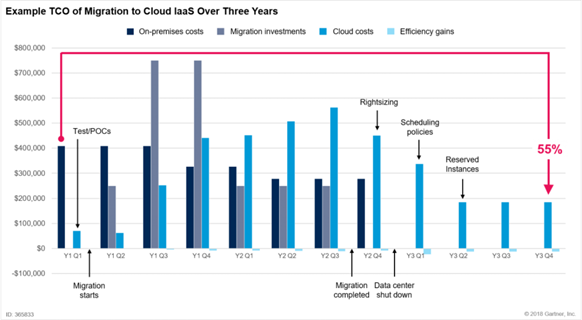

Step 3: Migrate quickly to cover the cost

As per our past experiences, we have seen the most cost-effective path to the cloud often, that approach ends up costing more in the long run. The reason is during migration organizations are bearing two infrastructures, incurring costs on both sides. If organizations want to cover the cost and begin to realize savings, then speedy migration with mitigated risks is the best approach for them. The statistics show organizations can see 40 to 60%*** operational cost savings when moving enterprise applications to a managed private or public cloud service.

Taking the next step to the future

Refactoring and repatriation are complex issues for organizations. But in most cases, cloud migration suffers because enterprises do not have the experience, knowledge, or resources to undertake the analysis, set the specific requirements, and make the best decision for the long term.

Now, cloud migration has become most crucial for digital transformation and for embracing to future technology trends. Therefore, it is the best time to enlist the expertise of your trusted partners can have a dramatic impact on your success.

If you are still confronting with the questions Refactor? Repatriate? Lift-and-shift? Then, it’s time to reach us to find out how the combination of cloud-first strategy and Azure technology platform can simplify your cloud migrations.

References:

*Gartner Forecasts Worldwide Public Cloud Revenue to Grow 17% in 2020 Retrieved from Gartner.com

**Malachy. J, (2019) Psst. Hey. Hey you. We have to whisper this in case the cool kidz hear, but… it’s OK to pull your data back from the cloud Retrieved from TheRegister.com

***Pierrefricke (2019) 3 Steps to Simplify Application Migration to the Cloud Retrieved from Rackspace.com

The public cloud is fast becoming the platform of choice for IT leaders and their line-of-business counterparts. While the pace of the move to on-demand IT continues to quicken, CIOs are faced with a bewildering option of providers and services. The absence of a common framework for assessing Cloud Service Providers (CSPs), combined with the fact that no two CSPs are the same, complicates the process of selecting one migration tool that is right for your organization. Majority rely on public cloud infrastructure due to a shared responsibility model such that the cloud service providers take care of the cloud itself while you focus on what’s in the cloud i.e. your data and applications. But how do you choose which public cloud provider will be helpful to your organization?

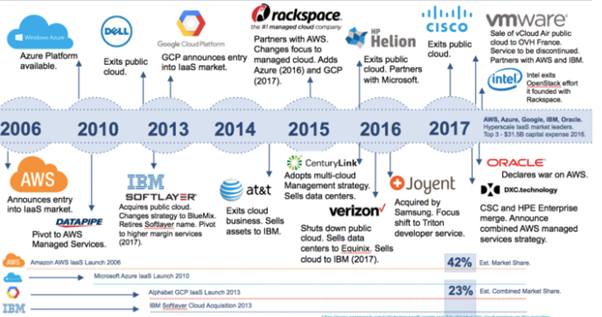

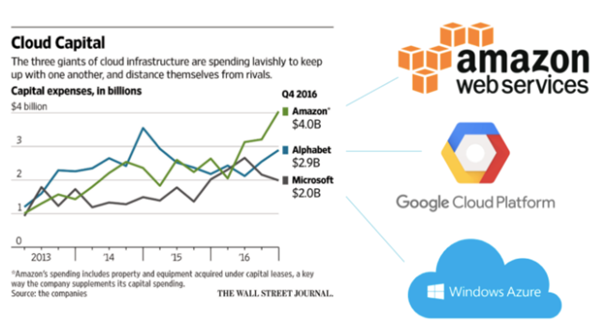

The field has a lot of competitors in it – mainly Amazon Web Services and Microsoft Azure dominate the cloud industry. AWS has been in the game the longest, capturing about 33%* of the market share with Microsoft in the 2nd position with 13% market shares. A superficial glance might lead you to believe that AWS has an unprecedented edge over Azure, but a deeper look will prove the decision isn’t that easy.

AWS has always had an unprecedented upper hand as it was first launched in 2002, whereas Microsoft did not step into the Cloud market till 2010. Azure was not very well received at first and there were many challenges as AWS had more capital, more infrastructure, and better, more scalable services than Azure did. Moreover, Amazon added more servers to its cloud infrastructure and made better use of economies of scale. This was a setback for Microsoft, but the tide soon changed. Microsoft revamped its cloud offering and added support to a variety of programming languages and operating systems. Thus, making their system more scalable and now Azure is one of the leading cloud providers in the world.

Both Azure and AWS technologies have, in their own way, contributed to the welfare of society. NASA used the AWS Platform to make its huge repository of pictures, videos, and audio files easily discoverable in one centralized location, giving people access to images of galaxies far away. The Azure IoT Suite was used to create the Weka Smart Fridge, – an implementation of the Internet of Things as a medical device to improve the storage and distribution of vaccines throughout the supply chain, in healthcare companies. This has helped non-profit medical agencies ensure that their vaccinations reach people who otherwise don’t have access to these facilities.

To determine the best cloud service provider, one needs to take multiple factors into consideration, such as cloud storage pricing, data transfer loss rate, and rates of data availability, among others. A few principal elements to consider for almost every organization while choosing the right tool to migrate are:

Security – Consider what security features are offered free out-of-the-box for each vendor you’re evaluating, which additional paid services are available from the providers themselves, and where you may need to supplement with third-party partners’ technology. Most tools make that process relatively simple by listing their security features, paid products, and partner integrations on the security section of their respective websites. Security is a top concern in the cloud, so it is critical to ask detailed and explicit questions that relate to your unique use cases, industry, regulatory requirements, and any other concerns you may have.

Compliance – Next make sure you choose a cloud architecture platform that can help you meet compliance standards that apply to your industry and organization. Whether you are beholden to GDPR, SOC 2, PCI DSS, HIPAA, or any other frameworks, make sure you understand what it will take to achieve compliance once your applications and data are living in a public cloud infrastructure. Be sure you understand where your responsibilities lie, and which aspects of compliance the provider will help you check off.

Architecture – When choosing a cloud provider, think about how the architecture will be incorporated into your workflows now and in the future. if your organization has already invested heavily in the Microsoft universe, it might make sense to proceed with Azure, since Microsoft gives its customers licenses and often some free credits. If your organization relies more on Amazon, then it may be best to look to them for ease of integration and consolidation. Additionally, you may want to consider cloud storage architectures when making your decision. When it comes to storage, both AWS and Azure have similar architectures and offer multiple types of storage to fit different needs, but they have different types of archival storage.

There are many motivations for evolving from an entirely on-prem infrastructure to a multiple or hybrid cloud architecture. From the very beginning of the cloud adoption process, hybrid cloud architectures allow enterprises to benefit from cloud economics and scalability without compromising data sovereignty. A multi cloud storage deployment also brings many benefits to the enterprise cloud, from avoiding vendor lock-in to accommodating mergers and acquisitions and optimizing price/performance.

Service Levels – This consideration is essential when businesses have strict needs in terms of availability, response time, capacity, and support. Cloud Service Level Agreements (Cloud SLAs) are an important element to consider when choosing a provider. It’s vital to establish a clear contractual relationship between a cloud service customer and a cloud service provider.

Costs – While it should never be the single or most important factor, there’s no denying that cost will play a big role in deciding which cloud service provider you choose. It’s helpful to look at both sticker price and associated costs. For AWS, Amazon determines price by rounding up the number of hours used. The minimum use is one hour. Azure bills customers on-demand by hour, gigabyte, or millions of executions, depending on the specific product. Serverless computing is a new cloud computing execution model in which the cloud provider runs the server, and dynamically manages the allocation of machine resources. Pricing is based on the actual amount of resources consumed by an application, rather than on pre-purchased units of capacity.

While the criteria discussed above won’t give you all the information you need, it will help you build a solid analytical framework to use when you are determining which cloud service provider you will trust with your data and applications. You can add granularity by doing a thorough analysis of your organization’s requirements to discover additional factors that will help you make an informed decision. This will be key to determining which provider will be the one that can deliver the features and resources that will best support your ongoing business, operational, security, and compliance goals.

References:

*How to choose your cloud provider: AWS, Google or Microsoft? Revived from : ThreatStack.com

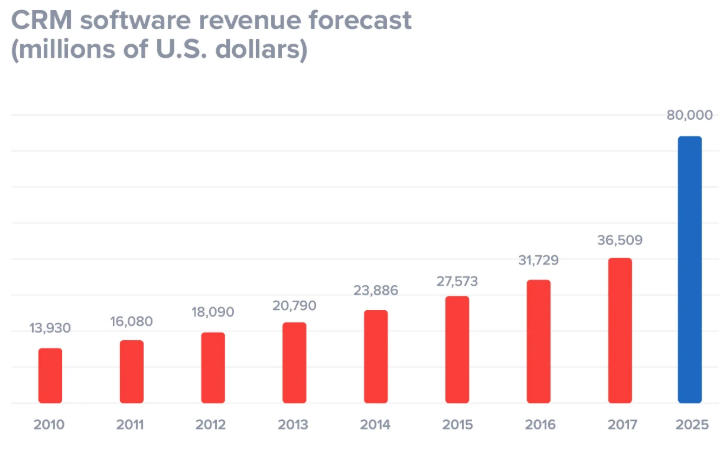

CRM (customer relationship management) has become a real buzzword in the 21st Century business world. If you never used this term before then, you might have heard it echoing in every business domain. When your business looks at every transaction through the eyes of the customer, then you must believe in the simple philosophy of CRM, “put the consumer first,” to increase loyalty for your company.

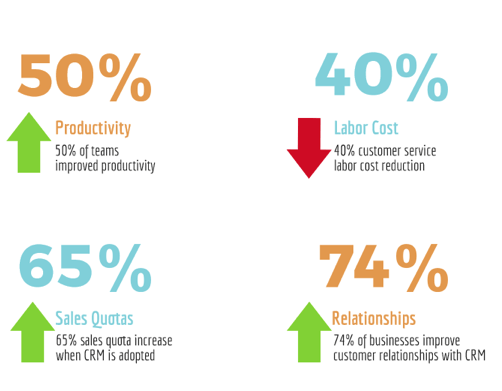

Now, it does not matter if your company employs 10 people or more than 100 people- CRM software can establish a closer connection with customers, provide professional customer services, and grow business further. Now, 72%* of companies have started investing in modern technology, such as CRM, in demand for better ROI.

What is cloud CRM?

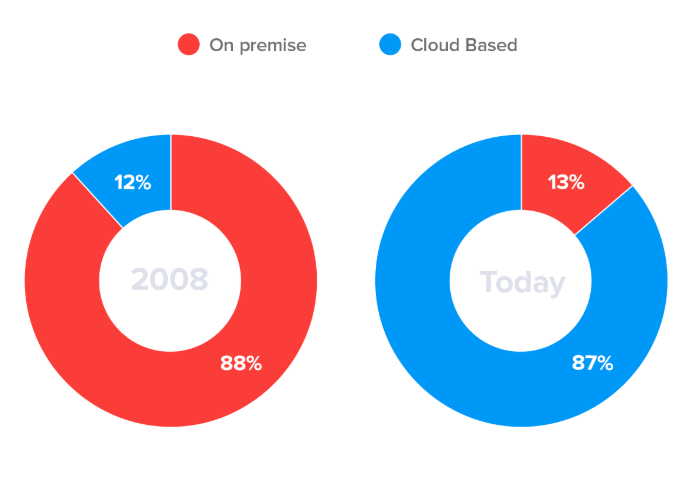

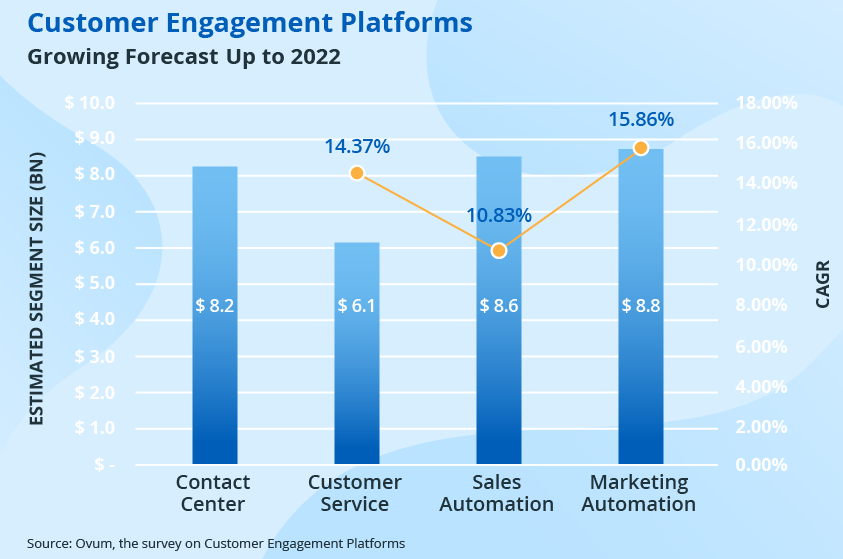

Traditional CRM systems were in-house applications, but today newer systems are cloud-based, which means the application and data both are held on the CRM providers’ servers in a datacenter and accessed via an internet browser. This cloud-based CRM or Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) CRM has lots of technical and financial advantages. According to The International Data Corporation (IDC) reports, IT Cloud services have seen an impressive lift-off in 2020, which stands for a 23%* growth compared to the previous five years.

In other words, things have changed a lot even the word ‘software’ has moved to the cloud from its old earth-bound domain because it is the exact place where businesses should look for the CRM solution.

10 benefits of cloud CRM:

1. Hassle-free installation

The fear comes first in the mind of the business decision-maker that CRM comes with a complicated installation process. But it is no longer valid. The modern cloud-based CRM is worry-free even, no business case is required for it.

There is no need for hardware and software maintenance or even a permanent IT person on site. You can complete the installation, migration, and system upgradation remotely.

2. No Upfront Cost

Anything cannot get easier than cloud CRM usage. After buying the software packages, all you need to do is log-in with access code, ensure uninterrupted fast internet connection from everywhere, and arrange a device to perform work.

Moreover, Cloud CRM operates on the pay-as-you-go subscription model, which requires a minimal upfront investment. There is no need for local servers to run the CRM system. So, there is no capital cost, no server software, and no maintenance. Monthly fee for a Cloud CRM package can be as low as €37*. By monthly or quarterly payment, you can reduce the financial risk and improve your company’s cash flow

3. Enterprise Grade Security

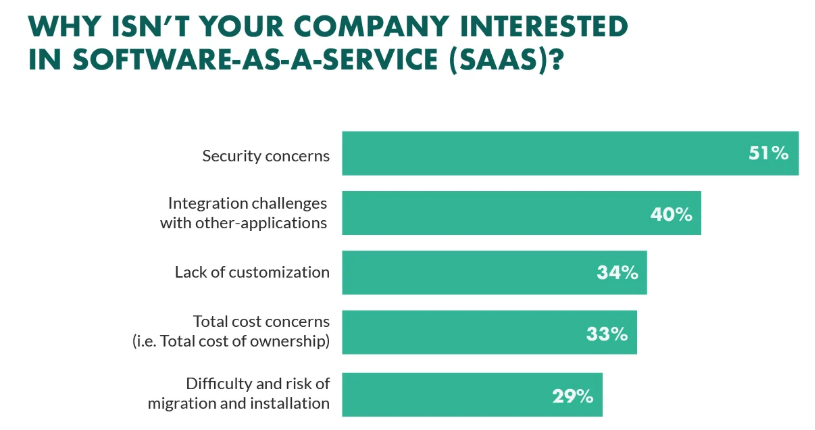

Security is a serious concern of every business using web-based information storage. According to Forrester Research, 51%* of businesses are wary of use cloud solutions known as SaaS due to security concerns. Web CRM data is always stored in redundant regional data centers, that would not cause downtime or data loss for problems at one data center. Governing data centers and the policies are certified with ISO-27001 as well as being certified by the Cloud Security Alliance (CSA), Cloud Computing Matrix (CCM).

These can be hosted on Government cloud (gov-cloud) as well if it’s a government or federal organization. Online CRM providers are much aware of all security issues and offer advanced automatized back-up policies that have clear data recovery plans if a breach happens.

4. CRM on the Move

Accessibility of the system is all-important for the salesperson so; they want some platform that could enable them to interact with the CRM tool in a seamless fashion. Round-the-clock accessibility is the immense benefit of Cloud-based CRM because this platform permits us to gain access from everywhere, in anytime with internet connectivity.

It is reliable to make some urgent, yet game-changing sales call, or send an amended sales proposal, or find a contact’s number or send an e-mail from any device when you are out of the office.

5. CRM, Power of collaboration

Within the cloud CRM framework, users can work jointly without any interference. It accredits unique login credentials to each team member that makes it possible to open multiple accounts all at once. Every cloud-based CRM is associated with thousands of partners that build a collaborative ecosystem. Dynamics CRM has office 365 and other partners that create strong networking in the whole ecosystem and bring the power of collaboration. This collaborative system improves customer interaction by availing customer data across teams for multi-channel interactions and retaining existing clients.

6. Advanced AI capabilities and Dynamic Dashboard

AI apps across customer service and sales are the latest online capability of cloud CRM software not available in OnPremise. Moreover, the organization insight dashboard will give you a visual representation of how your business is performing in the market. Users can analyze market trends, clear up the quantities, calculate the activities, and build their dashboard with easy instructions. It will help to inspect the performance of your team directly on the dashboard.

7. Effective to employee productivity

A cloud-based CRM program increases productivity in the workplace because it allows a team to operate more efficiently without being fastened to the office desk while tracking its customers. It also highlights the pace of team engagement with customers to derive feedback. With real-time data collection, it speeds up delivery of actionable leads and increases productivity levels across the board.

8. Reliable operation

Every business needs to maintain a lot of confidential customer information, and they require a system that allows periodic data back up and easy access in case of system break down. Incidents like data crash almost never happens with Cloud CRM as all parts of the cloud are backed up. In fact, a web-based CRM system maintains operational efficiency 99.99%* of the time with a robust data recovery process if any data breach occurs.

9. Endowed with agility

All virtual business components may affect software agility. But Agile cloud CRM software enables continual system access regardless of the device and makes users capable of certain changes as per the convenience.

10. Adaptable integration process

In a modern business environment, demand for flexible integration is on top. Cloud CRM can be integrated easily with other applications or software, such as Gmail and Office 365 products, including MS Office. That makes Cloud-based CRM an even more appropriate choice for your business.

Online CRM in workforce management during global pandemic

The novel-coronavirus pandemic is marked by uncertainty, and employees are adopting new ways of working to operate the business during the pandemic. A CRM can offer a 360-degree view of clients and stakeholders and take quick steps to address critical issues to establish best practices. The addon functionality of cloud CRM scales up marketing functionality with personalization capabilities and provides self-service rollout plans in response to COVID-19.

Furthermore, an automated CRM system makes employee remote work more collaborative with a customized database for interacting with potential target audiences. It is the time to empower your staff with result-driven software tools like cloud CRM and uphill your brand during this global crisis.

Reference:

* Plaksij. Z, 8 REASONS TO CHOOSE CLOUD-BASED CRM FOR YOUR BUSINESS Retrieved from: https://www.superoffice.com/blog/cloud-based-crm-for-small-business/

“Cloud is about how you do computing, not where you do computing.”, rightly said by Paul Maritz, CEO of VMWare

The corona virus quarantine has made a lot of organisations across various industries establish remote operations and not all companies are able to handle the forced move to a virtual office. Before the impact of the Corona virus, only 62* percent of the workloads were in the Cloud but as per 87 percent of the IT decision makers, 95 percent of the workload will be in the Cloud by 2025. This acceleration was fuelled by Covid-19 acting as a catalyst for cloud migration.

The current state of remote work was largely unforeseen, no disaster recovery plan included anything for a mass outbreak of a virus. This transition to remote work on such a massive scale would not have been possible in the server-led infrastructure 15 to 20 years ago. Large enterprises can now deliver new services 30 to 60** percent faster through cloud migration. After several months into quarantine, organisations have started refining and optimising workloads into the Cloud. When and how businesses will be able to resume on-premise activities at the office remains a big question.

The cost of cloud migration was one of the major reasons for many companies to not migrate to the Cloud. But, the current circumstances have led some of the organisations around the globe to renew their efforts to get into the public cloud. It is time one stops thinking about everything being a corporate owned machine, in a corporate office, rather utilise the opportunity to focus on virtualisation of servers, storage and networks. At this crisis time, virtualisation needs to be brought to end-user devices and Mobile Device Management has to be something every company needs to think about.

Though corporate IT resources are built to offer high levels of security, quarantines mean that direct, in-person access to them is limited if not completely unavailable. Enterprises considering digital transformation prior to the pandemic might have only wanted to move up to 30-40*** percent of their existing infrastructure to the public cloud. But now, more than 70** percent of executives have indicated a belief that cloud will help them innovate faster while reducing implementation and operational risks.

Long term plans for organizations may include use of public cloud, mobile computing, and moving to 5G wireless network. This allows companies to operate anytime and anywhere, which is much easier for born-in-the-cloud companies. Large enterprises cannot move nimbly, but the circumstances have shown the need for rapid changes beyond static systems with datacentres. Organisations that embrace flexibility will be able to recover faster than their competitors.

The entire process from start to finish, requires significant changes and change management with how an organisation’s teams interact, process and share their data amongst each other. The sweeping global transition to remote work has seen virtual collaboration tools thrown into the spotlight of economic activity and their demand has sky-rocketed.

“Beyond the emergency action needed at the start of the pandemic, many organizations have turned to mitigating risk through flexibility of infrastructure”, says David Linthicum, chief cloud strategy officer with audit and consulting advisor Deloitte.

While cloud adoption offers a powerful opportunity to unlock business value, there remains a distinguishable hesitation around a few challenges of this transition. Cybersecurity is the biggest concern and remains a significant barrier when companies think of migrating to the cloud. Security threats have increased substantially during Covid-19, and organisations need to recognise and respond. Advanced cybersecurity solutions are now available which can help boost the security architecture.

Cloud computing, which has been touted for its flexibility, reliability and security, has emerged as one of the few saving graces for businesses during this pandemic. Its use is critical for companies to maintain operations, but even more critical for their ability to continue to service their customers.

Cloud adaptation provides an avenue of growth which can help balance the economic challenges faced by various organizations. Cloud budgets today account for approximately 5** percent of the average IT budgets, a figure that is likely to double by 2023.

As organisations have started adjusting to the new reality of the pandemic, cloud adoption represents a multi-billion-dollar opportunity for businesses in every region of the world. The world will eventually emerge from this period of remote work, but the way we do business will be transformed forever.

References:

*Sead Fadilpasic : Cloud migration set for major rise following pandemic, June’20. Retrieved from ITProPortal

**Luv Grimond and Alain Schneuwly : Accelerating Cloud Adoption After Pandemic, June’20. Retrieved from Jakarta Globe

***Joao-Pierre S. Ruth : Next Steps for Cloud Infrastructure Beyond the Pandemic, April’20. Retrieved from Information Week

Not to name names, but I’ve been reading in several publications that one of the main reasons to go to multicloud is to avoid vendor lock-in. While I can see the logic behind this assumption—that having more cloud providers means you can be more independent—the reality is much different.

For example, if you have an application in the cloud, and you’re using a multicloud architecture, you’ll have two or three choices where to place that application workload and associated data: Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, and/or Google Cloud Platform.

You’ll pick one cloud for that application and do the standard migration processes to get it up and running. What most people don’t understand is that, as part of that migration, you’re likely to make the application workloads cloud-native. That means you’re going to alter the applications, slightly or heavily, to take advantage of the native cloud services, such as API management, governance, security, and storage.

By altering the application to be cloud-native, you’re locking yourself in to that cloud provider, for that application. If you don’t go the cloud-native approach, it’ll be easier to migrate that applocation to a different provider later—but at the price of a suboptimal deployment due to not being cloud-native.

You have to make a trade-off between using advanced application capabilities (cloud-native), and thus also accepting vendor lockin, or keeping the app geberic and less optimal to avoid that lockin. It does not matter if you’re using a single-cloud architecture or a multicloud architecture, the lockin trade-off is the same.

In this 60-second video, learn how the cloud-native approach is changing the way enterprises structure their technologies, from Craig McLuckie, founder and CEO of Heptio, and one of the inventors of open-source system Kubernetes.

IT INSIGHTS

What is the cloud-native approach?

Of course, it is an advantage to have another public cloud connected and integrated into your architecture so that other public cloud options are available if and when needed. But you still have to make that same trade-off between being cloud-native and avoiding lockin.

Of course, it is an advantage to have another public cloud connected and integrated into your architecture so that other public cloud options are available if and when needed. But you still have to make that same trade-off between being cloud-native and avoiding lockin.

You might think you can avoid the trade-off by using containers or otherwise writing applications so they are portable. But there is a trade-off there as well. Containers are great, and they do provide cloud-to-cloud portability, but you’ll have to modify most applications to take full advantage of containers. That could be an even bigger cost than going cloud-native. Is it worth the avoided lockin? That’s a question you’ll need to answer for each case.

Moreover, writing applications so they are portable typically leads to the least-common-denominator approach to be able to work with all platforms. And that means that they will not work well everywhere, because they are not cloud-native. I suppose you could write portable applications that are cloud-native to multiple clouds, but then you’re really writing the application multiple times in advance and just using one instance at a time. That’s really complex and expensive.

Lockin is unavoidable. But lockin is a choice we all must make in several areas: language, tooling, architecture, and, yes, platform. The key is to choose each lockin poont wisely, to mimimize the need to change horses. But when a change must happen, there’ll be a price to be paid. If you make the right choices, you’ll pay that price not very often, and you”ll have gained more from those choices in the meantime than you would have gained from a least-common-denominator approach